the

Model 1927

Irish

Free State Helmet

Background

and History:

Brief

Background of the Conflict:

After centuries of conflict with the English and

spurred on by the Easter uprising of 1916, with the 1919-21 War of Independence

the Irish gained their independence. This was only to be followed by further

violence and the Civil War of 1922-23 over the volatile question of the

division of the country into the separately governed Northern and Southern

States. When finally resolved in 1923, the Irish Free State and Northern

Ireland were born and closely took on, for better or worse, the shapes

they have today. When the questions of governing were settled it was time

to organize the traditional branches of government, one of these being

the military. Thus, the Irish Free State army was born. It should be mentioned

that in 1949 the status of Irish Free State was changed to Republic of

Ireland.[1]

Figure 1: Michael Collins.

Equipping of Irish troops and military units of

all sides (excluding the British) of the controversy during the Rebellion,

Civil War and following Free State period, was very interesting and

often comprised any and all materials available. It began during a time

(1914-18) when huge demands were being made on all of the world’s armies

and there was little to spare. The photographic evidence and surviving

historic materials bear this out. The assemblages of rifle from the period

are comprised of obsolete Italian Vetterli-Vitali, German Model 1871 Mausers

and Russian Model 1891s. Many of these were kindly provided by the German

government in ongoing attempts to divert British troops from the Western

Front where they were in direct conflict with German troops. Uniforms consisted

of whatever could be brought by individuals or obtained locally. Much of

the material was of British origin.

Figure 2: The Fighting 2nd - 1923.

History

of the Helmet:

When the process of selecting a suitable helmet

began, it would prove to be one that years later would provide the collector

with a story whose history was not only rooted in the struggle for Irish

freedom, but also deeply entwined within the greater world-wide conflict

of 1914-18. Still bearing a slight dislike for items of British origin,

the tin hats of British design were not at the top of the Free State’s

list when it came to choosing a helmet. The French Adrian design was tried

and found to be unsatisfactory. Finally, the German M16 design was settled

upon and the German Counsel approached. However, because of the provisions

in the Treaty of Versailles the Germans were forbidden from exporting military

materials including helmets.

So, it was back to the Brits, who just happened

to find themselves in possession of surplus German helmet manufacturing

machinery and, who would be willing to contract for manufacture, (through

the auspices of Vickers, Ltd.), of the German Model 1916 style helmets

for the Irish Free State government.[2]

Thus, the circle seemed complete, and as we shall see in the following

evaluation with some interesting results. A total of 10,021 helmets were

made for an Irish Free State standing army of 10,000.

Intentionally or otherwise, the helmets were made

with an inferior quality material. Anyone handling a standard German or

Austrian helmet of the Great War period, then handling a Model 27 will

easily recognize the difference in weight and feel. The stress lines along

the front of the helmet are prominent, and many cracked and became unserviceable

during their period of use. One must wonder about motivation, as it had

been only a brief period of time since the last British troops left the

island. Stranger yet, one must wonder why the Irish Free State was willing

to take delivery of helmets that did not standards. Although a review of

the army’s history reveals a great deal of controversy over the organization.

Funding was also a problem during the period.

Figure 3: Military Mission to the US - 1926-1927.

The official period of use for the M27 was from

1927 to 1939, when a change of heart took place and Tommy’s helmet was

adopted. This was no doubt in part due to the events taking place on the

continent at that time. While officially a neutral country during the period,

a large number of the helmets were painted white and issued to Civil Authorities

during WW2. These are the helmets that most often appear on the collector’s

market today. They also appear with a black coating of paint, of unidentified

origin, over the white.

The helmet did not undergo an extensive “trial-by-fire”

during its tenure. However, the limited production, attrition due to inferior

quality, the wholesale destruction of more than half of the original production

(as helmets were bulldozed into the ground in the 1970’s for fill for a

new army barracks) by the Irish army,[3]

and the subsequent deterioration have all combined to make the Irish M27

one of the more obscure, difficult to find and sought after helmets by

the collector.

Evaluation:

This

particular Model 1927 helmets arrival was a thrill and an eye-opener. It

was a scarce helmet with the appearance of 30 years of storage in a barn

or loft and one of the Civil use helmets with the coating of white paint

applied in 1940. While finding a helmet in untouched condition is my preferred

option, it was obvious from the start that in this case the benefits may

well be tempered by other conditions at work beneath the white overcoat.

Figure 4: Interior before restoration.

The examination began with the outside. First appearance gave the impression of an extensive build up of dirt and grime, an easily remedied situation. However, a closer examination revealed that the crackled white paint displayed less of what appeared to be surface build-up and more of what looked like rust seeping through from beneath. This appeared to be the situation across the entire exterior. There were several small areas where the white paint had come off and the original black-green was present, and other areas where the same was true but a rusted surface appeared to be present.

The interior, lower edge of the shell was painted white and exhibited the same pattern as the exterior. Above the liner it had not been painted white, other than some overspray from where the liner was pulled away during the painting operation. This was fortunate, as it would provide the only true reference I would have regarding the actual color and current state of the original finish that lay underneath the white overcoat. Something that would be much needed later. The liner was in fine shape but extremely dry. All of the stitching was intact, as well as all of the pads, sewn cloth pad cases and the brass retaining fixtures. The liner was obviously made of high quality leather, with the band being very thick material and the tongues being of a very thin but fine quality. There was very little white paint on the liner. This would be the easy part!

After removing the liner pads and the chinstrap, a light cleaning with a mild detergent was performed, followed by a stronger cleaner and then by a cleaning with a light weight penetrating oil and #0000 steel wool. While a certain amount of built up dirt and grime, and some surface rust was removed with the initial cleaning, it was clear that the majority of the deterioration was taking place beneath the coating of white paint. The telltale evidence was seeping out at the crackled edges and any attempt to permanently retard the destructive process and save the original finish (if any remained!) would require the careful removal of the 1940 coating.

Shell

and liner markings:

Shell Stamps:

The shell and liner each have a single set of markings.

The shell is stamped on the inside back edge, and it consists of two lines.

The upper line is stamped “V.LTD

H9142” while the second line is “H 40 / ‘27”. The first line can

be read as “V” for Vickers, “LTD”

for Limited, and the “H9142” for “Helmet and serial number, or production

number.” This is particularly interesting in that the total number

of helmets produced is known to be 10,021, so any individual helmet can

be identified as to its’ place in the production process. For instance,

this helmet is number 9,142 out of 10,021, one of the later helmets in

the production run. Makes you wonder what the earlier ones were like?

Figure 5: Shell stamp.

The second line of the stamp is also interesting because it was original to the helmet when made, but added at the time the helmet was painted white and issued for Civil Duty in 1940. This is indicated by the H 40 designation. Also confirmed by this set of stampings is the helmets original designation as the Model M1927, with the “H40/’27” stamp.

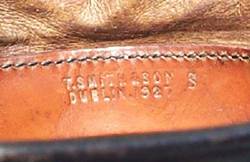

Liner Stamps:

While the helmet shells were made by Vickers, the liners were made in Ireland, from very high quality leather. The manufacturer was “T. Smith and Sons, of Dublin.” Their stamp is found on the liner band, by lifting up the front pillow of the helmet. As can be seen in the photo, this is documented with a two line stamp, consisting of the name, location and again the 1927 date followed by the size indicator, S, M, or L for the obvious small, medium or large size liners.

Figure 6: Liner stamp.

Pad Markings:

The final mark to be found on the helmet, are the ink stampings on each of the liner pads. Each pad is stamped in ink, “Hilton Bros. 27” over a large number 1, 2 or 3. Obviously the Hilton Brothers were the proud makers of the liner pads, and the ‘27 is another reference to the 1927 model number. But, there doesn’t seem to be any difference in size, or any reason to differentiate between the pads, so the purpose for sequentially stamping the set of pads “1,2,3” remains a mystery.

Figure 7: Pad markings.

The

Components and construction:

Chinstrap and Chinstrap Bolts:

The

chinstrap, like the liner band is of very thick leather. The hardware is

crudely cast aluminum and is very thick also. The bolts are near duplicates,

and based upon the evidence below most likely spare parts, from German

M16 helmets. The chinstrap hardware is permanently mounted to the lugs

and cannot be removed. How the hardware was fit over the lugs originally

is unknown, but it must have been before assembly or by heating the piece

and sliding it over the lug in the heated stage. The leather strap bears

this out, as it has been thinned at the end for ease of removal, the evidence

of it having been resewn several times supports this.

Crest:

The crest worn on the front of the helmet is a variant of the Model 1924 Officer’s Cap crest. There is a distinct difference in the construction of the 1924 cap badge and the 1927 helmet badge, in the attachment prongs on the back. Most of the crests seen on helmets today, and indeed the one featured in this article are cap badges with the prongs bent downward. Original helmet crests are as rare, or perhaps rarer than the helmets themselves. The modified 1924 cap badge if carefully prepared, works well for display purposes.

Figure 8: Helmet crest.

Originally the crest was painted black. The outer inscription is Gaelic, “Oglais na hEireann” for IRISH DEFENCE FORCES, as first defined by the Irish Volunteers in 1913. The inner initials of he crest, “FF” stand for “Fianna Fail” the Republican movement. It appears the crest was worn only during military service.

Liner:

The liner is made from high quality leather. Produced by “T. Smith & Sons of Dublin” and so marked on the band, beneath the front finger. The leather band is very thick, while the fingers are a very thin but strong material. To hold the pads, cotton pockets are sewn onto each leather finger. Three ¼” flat copper rivets with 9/16” copper washers permanently fasten the liner to the shell.

Figure 9: Liner after resoration.

Lugs:

An extremely interesting feature of this helmet is the helmet lugs. There are two stepped lugs following the German M16 pattern. However, unlike the German method where the lugs are used as a sizing indicator for the helmet, each of the M1927 lugs is of a different size and configuration!

Figure 10: Lug comparison.

This has two connotations. One, which is very interesting, that the Vickers LTD. company was using spare German parts. Two, the reason for the difference in sizes was not understood, or was disregarded. The larger lug is the where the indentation in the shell mentioned above occurs, making the manufacturing scenario the most likely.

Figure 11: Lug dent.

In the original German M16, the lugs performed as vents and as mounts for an armoured visor. During it’s tenure with the Irish Free State, no such visor was employed with the Model 27 helmet.

Pads:

The pads are made of a gray canvas or canvas-like material and marked as above. The filler material is most likely horsehair. However, it has an extremely stiff and coarse texture, almost of a straw-like consistency. None was removed for verification, but it makes one wonder if the traditional sedge roofing material may not have been used. Then again, if it were the hair of the Connemara Pony, the extraordinary stiffness could easily be accounted for by the unbelievable speed with which the wind would have passed over it.

The ties that accompany the pads are of three different lengths and one of a different material.

Figure 12: Pads and ties.

Shell:

The shell is made from low grade steel. This has been referenced in printed materials and is visible in the stress lines and cracks occurring in the front of the shell. In addition, the overall workmanship is substandard. Whether due to the unfamiliarity with the machinery of lack of incentive is anyone’s guess. However, viewing the shell from the front the front to back alignment is off, and by running one’s hand across the surface numerous minor irregularities can be felt. In addition, there is an indentation surrounding the right side lug, either from an impact or most likely it is a result of production process. The difference in weight, heft and overall quality between the Irish M27 and a traditional German M16 can easily be felt by holding one of each.

Figure 13: Shell exterior.

An examination of the original paint in the crown beneath the liner illustrates a plate-like separation with rust and corrosion taking place. The original paint is very thin and it is difficult to determine if there was much effort to harden the finish. Neither the quality of the shell, nor the finish on the shell approach that found on the German Model 1916 helmets.

On the front of the helmet, and one of it’s most distinguishing features, are two brass mounts held in place with 1/16” dome head rivets. These are the retaining mounts for the M1924 Officers Pattern crest.

The

Restoration process:

Restoration began with the removal of as many components

as possible. In this case, because the liner was permanently fastened to

the shell, it included the chinstrap, pads and pad strings. Next, the leather

was treated to two coats of a high quality preservative to protect it from

any contact it may have with the liquid materials that would be used to

work on the shell. The leather preservative was allowed to dry before starting

on the metal.

The materials used to work on the shell included,

a chemical stripper, several old toothbrushes, #0000 steel wool, a mild

laundry detergent, plenty of cold water, light weight penetrating oil,

lots of rags, tons of patience and much more time than was available.

Work began on the inside, on an out of the way location,

where the least amount of harm could be done, and where the worst fears

were realized. Not only did the stripper remove the white overcoat, but

the original dark matte, black-green coat (which fortunately was still

there) was very unstable and also was easily removed. This meant only a

small area at a time could be worked upon, and it would require carefully

qauging the time it would take the chemical to interact with the overcoat,

then quickly removing it, stopping the reaction and stabilizing the area

before proceeding to the next area.

This then was the process that was followed over

the entire shell, inside and out, using a combination of toothbrush and

steel wool, depending upon the thickness and accessibility of the region.

The original finish was so thin in places, and combined with the rusting

that was taking place beneath the white overcoat, there were times it felt

like a hopeless cause. Admittedly, there were several times it felt like

a bad decision had been made.

Whether it was the quality of the steel or the original

finish interacting with the materials being used, or perhaps a bit of some

wily leprechaun’s trick, as an area would become finished it would appear

to completely change color. Being somewhat familiar with light and it properties

(having worked for years in the optics field) there was an awareness of

what might occur as a result of changes in light and materials, but this

was baffling. There were times when the finish took on a cold steel appearance

one would swear the entire finish had been removed, and other times when

the color appeared to be completely changed. This then, only to be presented

the next morning with a helmet that retained 80% of its original finish.

Definitely not for the faint of heart!

Figure 14: Partially reworked exterior.

Following the removal of the overcoat, the rust had to be stabilized. This was accomplished with light weight penetrating oil. The rust was loosened and then wiped away. The amount of rust that came off when wiped with clean rags was quite something to see. Again, the area was stabilized with soapy water as the oil also loosened the original finish. The entire shell was completely dried to prevent any further rusting and a light coat on non-penetrating oil applied the wiped clean. This was followed by a light buffing with #0000 steel wool, replacement of the liner parts, and you have the helmet as shown below.

The

Final Product:

A light touch and patience are the key ingredients throughout the entire process. Without either of these you can easily end up with a plain steel shell. The results were quite pleasing, with an estimated original finish of between 75-80%.

The

areas that were rusting beneath the white overcoat are visible as rough

areas in the picture. These are now stabilized, and the helmet is displayed

in its’ original military configuration. It would be interesting to know

if there are other examples that exist is the original configuration. Perhaps

in the Dublin

in one of the National

Museums, or more

likely some rural farmhouse, there may be a souvenir that “escaped” the

crusher.

Figure 15: Finished M1927 - Front View.

Figure 16: Finished Model 1927 - Left Side View.

Figure 17: Finished M1927 - Front View without Crest.

My most sincere thank to those whose articles and information has been referenced. Please feel free to contact me with any questions or comments.

- Best Regards, Mike Sullivan

Additional

Links:

http://www.gostak.demon.co.uk/helmets/ireland.htm

- Greg Pickersgill’s Vicker’s M1927 Web Page

http://meltingpot.fortunecity.com/utah/894/irishm27.htm - The Irish model 1926 Helmet

http://www.military.ie - The Irish Defence Forces Web Site.