THE RIBBON COLLECTOR

A

newsletter for those who value the bits of colored cloth

and

similar or associated items made of other materials

intended

as awards of recognition in the

ISSUE No. 6

FEBRUARY 2018

>>>>>>

(This version has been modified and reformatted for compatibility with Webpage

display) <<<<<<

PUBLISHED BY

Garreteer Press (formerly Patriot Press)

Office of Price

Administration Awards

by Greg Ogletree

Executive Order 8875

established the Office of Price Administration (OPA) on 28 August 1941. It had initially been established on 11 April

1941 as the Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supply, but no awards are

known to have been created for its employees during the four and one-half month

interim before the name change.

The functions of the OPA were

originally to control money (price controls) and rents after the outbreak of

World War II. It became an independent

agency under the Emergency Price Control Act of 1942, signed into law on 30

January 1942. The OPA had the power to

place ceilings on all prices except agricultural commodities, and to ration

scarce supplies of other items, including automobiles, bicycles, tires, shoes,

nylon, sugar, gasoline, fuel oil, coffee, meats, and processed foods. At the peak, almost 90 percent of retail food

prices were frozen. The OPA could also

authorize subsidies for production of some of those commodities, and it controlled

wages.

The greatest challenge of such

massive war-related production was the permanent scarcity of resources. In response to it, the

On 1 January 1942 the War Production

Board ordered the temporary end of civilian automobile sales. Automobile factories stopped making cars and retooled

the assembly lines to produce tanks, aircraft, weapons, and other military

products, with the federal government as the only customer. As of 1 March, dog food could no longer be

sold in tin cans so the manufacturers switched to dehydrated versions. A month later, anyone wishing to buy

toothpaste, which was sold in metal tubes, had to turn in an empty one. By June 1942, companies also stopped

manufacturing metal office furniture, radios, phonographs, vacuum cleaners,

sewing machines, washing machines, and refrigerators for American homes and

began making war-related products. And

it wasn’t just vehicles and appliances that were affected.

Sugar was the first consumer

commodity rationed, with all unlimited sales ended on 27 April 1942. Coffee was next, with national rationing beginning

on 29 November 1942. As the war

progressed, ration coupons and tokens were used for many other items in

addition to gasoline, sugar, and coffee, including: butter, margarine, cheese, meat, lard,

shortening and food oils, processed foods (canned, bottled, and frozen), dried

fruits, canned milk, jams, jellies, fruit butter, fuel oil, wood-burning and

coal-fired stoves, bicycles, footwear, silk, nylon, and even typewriters—the

personal computers of that era. Board

permission was required just to rent a typewriter, regardless of whether the

rental was to a business or an individual!

The mobilization for war

brought unemployment to an all-time low of just 700,000 in the fall of 1944. The wartime production created millions of new

jobs, while the draft reduced the number of young men available for those jobs.

So great was the demand for labor that

millions of retired people, housewives, and even students entered the labor

force, lured by patriotism and wages.

The impact of this was far-reaching and, in many cases, permanent. For example, the shortage of grocery clerks

caused retailers to convert from service at the counter to self-service, with

customers using baskets to collect what they needed directly from the shelves. Also, before the war most groceries, dry

cleaners, drugstores, and department stores offered home delivery service. The labor shortage and rationing of gasoline

and tires caused most retailers to discontinue this service. An added bonus was discovering that having customers

buy their products in person after wandering through the aisles increased sales

as a result of what today is called impulse purchases!

Labor shortages were felt in

agriculture too, even though most farmers were given an exemption and few were

drafted. Large numbers volunteered or

moved to cities for factory jobs. At the

same time, many agricultural commodities were in greater demand by the

military, and for the civilian populations of allies. Production was encouraged and prices and

markets were under tight federal control.

In the thick of all of this was the OPA and its thousands of workers scattered

across the nation.

Because rationing had been expanded to include far more than just

tires, the three-person boards established initially were enlarged and, in most

cases, divided into panels devoted to just one rationed item or one group of

closely related items. Thus, the

original tire rationing board was divided into a tire panel and an automobile

panel, soon to be followed by a food panel, a gasoline panel, a fuel-oil panel,

and so on. Board size grew as the number

of rationed commodities grew. So, how

many people are we talking about? In an analysis

recorded in July 1944, one writer provided the following numbers:

In its

Volunteers serving on the OPA’s

War Price and Rationing Boards were identified by plastic lapel pins (Figure

1). These measured about one inch by one

inch and had a simple V-catch pin on the back for easy attachment to clothing.

Figure 1

All board members and most

board assistants (the number of assistants varied depending on locale) were

volunteers who served without compensation.

These people included politicians, businessmen, doctors, labor

representatives, factory workers, teachers, housewives, high school students,

and farmers. In most cases, they came

into the board offices to make their contributions of service after putting in

a full day at their own work. Generally

speaking, board members were decision-makers and board assistants were

functionaries. Assistants’ tasks ranged

from answering telephones, filing cards, and manning information desks (most

board offices were open daily, except Sundays, from 8am to 8pm) to issuing

gasoline rations and assisting price panels in their work of holding down the

cost of living. Most boards also had one

or two paid workers, who did the typing,

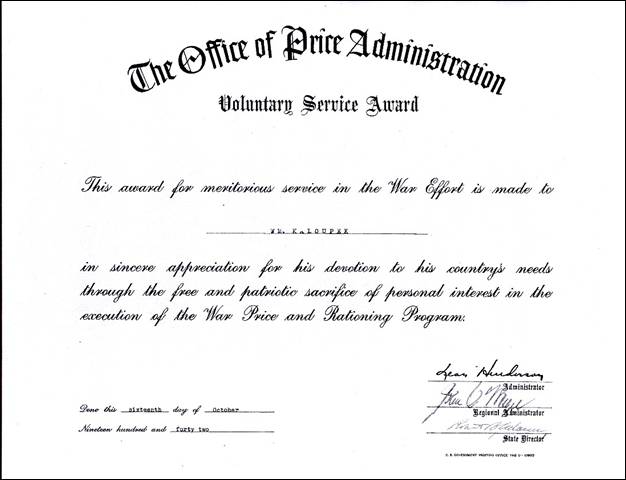

As the war progressed, someone

decided that OPA volunteers deserved more than just a plastic pin and a pat on

the back for their volunteer work in the War Price and Rationing Program so a

“Voluntary Service Award” certificate (Figure 2) was created in 1942. These certificates were signed by the OPA

Administrator, Regional Administrator, and State Director.

Figure 2

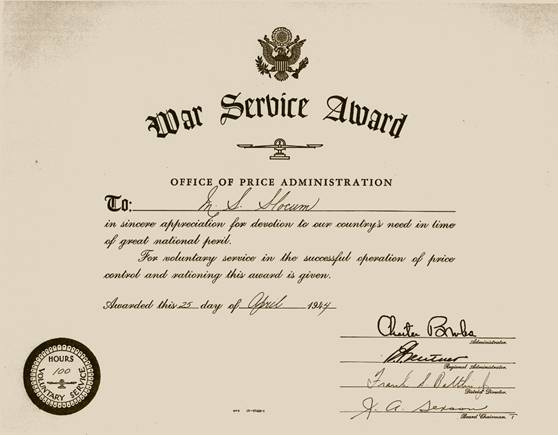

Before long, additional

recognition was bestowed in the form of a “War Service Award” (Figure 3),

presented to those who completed 100 hours of service, “with one seal added for

each additional 100 hours, or [for those] who have served for one year or

more.”[2] In spite of this statement, other sources say

additional hours were denoted using red ribbon:

“On the certificates for volunteers who have served 200 hours there will

be a red stripe diagonally across the corner, with an additional stripe for

each 100 hours.”[3] Certificates with additional seals or red

stripes have not been observed by the author so it is unclear which method was

actually used (or maybe “seal” was the term used for the red stripe?). These certificates carried the signatures of

the OPA Administrator, Regional Administrator, District Director, and the local

Board Chairman. The name of the

recipient, date of award, and the number of volunteer hours were entered by

hand on each certificate.[4] Not obvious to readers of this article who

can’t hold one of these certificates in their hands and therefore must rely on

what is seen in the illustration, below, is the fact that these certificates

are quite large, measuring 11 x 14 inches.

Figure 3

In

addition to a certificate, workers who donated 500 hours of volunteer service

were awarded an OPA Meritorious Service lapel pin (Figure 4). The pin is described as a “silver lapel pin”

in newspaper articles but observed specimens appear to be silver-toned and are

not marked

Figure 4

The

chairman of one of the local boards, who spoke at a presentation ceremony, said

of the volunteers who were receiving these pins:

It is a real honor to be part of an organization so

largely staffed with volunteers. In the

trials and annoyances so often associated with both rationing and price

control, the public sometimes forgets that the service rendered at our board

office is in most cases a voluntary contribution to the community war effort by

the clerk on the other side of the counter.

Without these local volunteers I doubt if the OPA programs could carry

on in [this city]. Now when someone

comes in to the board and sees a silver pin on the clerk, he will know that

this clerk has personally contributed over 500 hours of labor to our war

effort. This award is a real badge of

honor and can be worn proudly. I hope

that everyone recognizes the contribution these volunteers have made to all of

us.[6]

In

addition to being awarded to board assistants

for completion of 500 hours of service, these pins were also awarded to board members for meritorious service. In fact, far more pins were awarded to

recognize service by board members than were awarded to board assistants for

hitting the 500-hour mark. How

many? During the first week of January 1944,

when the first mass awarding of OPA War Service Award certificates (85,300 were

awarded) and pins occurred across the nation, 9,060 pins were presented to

volunteers for 500 hours or more of service, and 76,000 board members received

the pins for meritorious service, regardless of the number of volunteer hours

served—though it is likely that most, if not all, had served far more than 500

hours.[7] Once again, to be clear, all board members

were volunteers, serving without pay, and most—but not all—board assistants

also were unpaid volunteers. At the time

of the aforementioned mass awarding of certificates and pins, 234,000 people (i.e.,

assistants) worked with the price and rationing boards and, of that number,

about 200,000 were unpaid volunteers.[8] Given this information, we know that fewer

than half of the volunteers qualified for the certificates, but about an

equivalent number received the pins, so 170,360 received some type of special

recognition—about 85 percent of the total number of volunteers.

When

a volunteer worker reached the 1,000-hour milestone, an OPA war service ribbon

bar was awarded, with a silver “V” device added for each additional 500 hours

(Figure 5).[9]

1,000

Hours

1,500 Hours 2,000 Hours 2,500 Hours 3,000 Hours

Figure 5

As

the ribbons above show, awards were presented for as many as 3,000 hours of

volunteer service, and an individual wearing the bar with four devices could

have had as many as 3,499 hours of service.

It is not known if any volunteer ever reached the 3,500-hours mark, and

if so, how that was symbolized, but there is room on the ribbon for five “V”

devices on its blue portion, although none has been observed by the

author. One possibility is the use of

“X” devices to symbolize 1,000 hours, either alone or in combination with the “V”

devices, but no evidence of the use of “X” devices has been found so this is

mere speculation. Another possible

option for a very high number of hours is an entirely different type of award, something

other than a ribbon bar. That is

doubtful though, as the historical record is mum on that topic.

Wording in some newspaper articles that

publicized awards made to local OPA volunteers suggests the awards were created

late in the war. For example, an item

published in January 1945 contained the statement “…war service certificates,

recently made available by the Office of Price Administration…” and a companion

article in the same paper on the same date said, “…awards in the form of war

service ribbons and pins, lately made available by the Office of Price

Administration….”[10] However, the record shows that silver pins

and War Service Award certificates were presented to OPA volunteers as early as

July 1943.[11] Considering this, the probable time of

creation of the certificates and pins was early 1943, or possibly even sometime

in 1942. The ribbon bars, however,

appear to have been introduced later, probably late 1944 but definitely not

later than January 1945 when they were described in newspaper articles.[12]

Hopefully, OPA documents will eventually

surface that reveal the exact date(s).

Figure 6

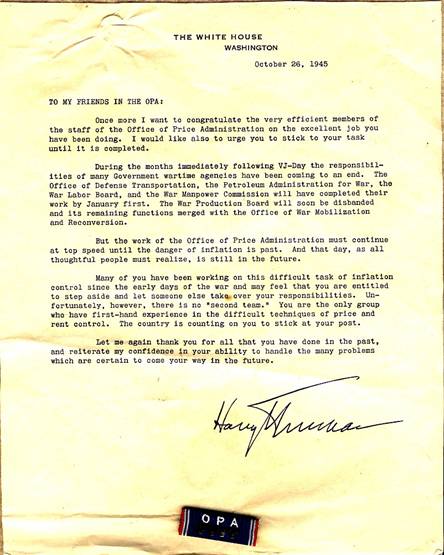

Unlike some other civilian ribbon bars

awarded during World War II (e.g., by the American Red Cross and the War

Department) that were often presented attached to or with an accompanying

document mentioning the award, that does not appear to be the case for the OPA

ribbons. However, a letter from

President Truman, dated 26 October 1945, addressed “TO MY FRIENDS IN THE OPA”

was the vehicle used to distribute OPA ribbons to recipients shortly after the

war ended. The ribbons were affixed to

the bottom of the letters, as seen in Figure 6, above. Even so, it’s important to note there is no

mention of the award in the text of the letter—it’s almost as if its inclusion

was an afterthought. One possible

explanation for this may be that not all recipients of the letter qualified for

an award (i.e., some had fewer than 1,000 hours of service).

Figure 7

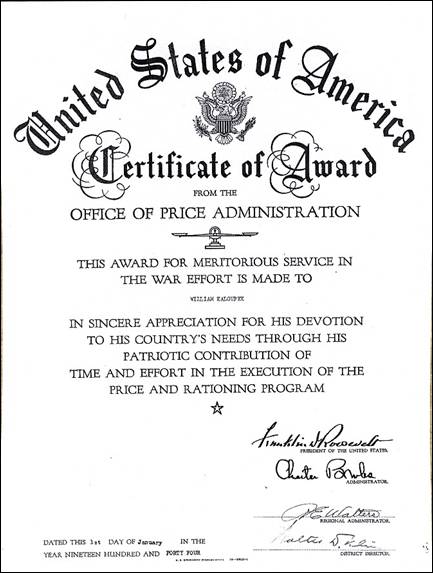

While

board assistants received a War Service Award certificate (Figure 3) for hours

served, board members received a Certificate of Award for meritorious service

(Figure 7). In addition to the portrait

rather than landscape format and the different wording, these certificates

carried the facsimile signature of our country’s president in addition to the

signatures of the OPA Administrator, Regional Administrator, and District

(i.e., state) Director. Indications are

that these were not awarded during the ceremonies conducted on the second

anniversary of the creation of OPA’s War Price and Rationing Boards, when the

pins were presented, but sometime later in January.[13] One of these certificates, awarded to a board

member in Maryland shortly after the war ended, was adorned with ribbons and

described as follows: “Across the upper

left-hand corner of the certificate are three half-inch satin strips, in the

national colors, one for each year of service.”[14] Others elsewhere may have been similarly adorned,

but as the certificate in Figure 6 demonstrates, not all were.

Following the end of World War II, most

functions of the OPA were transferred to the newly established Office of

Temporary Controls (OTC) by Executive Order 9809, 12 December 1946. The OPA was abolished on 29 May 1947 and its

remaining functions were assumed by various successor agencies. The only reminders of the OPA today are stories

told by some of the people who worked behind the counters; the certificates,

pins, and ribbon bars illustrated in this article that many of those volunteers

were awarded; and the memories of those on the front side of the counters who

endured the rationing and remember the price, rent, and wage controls enforced

by the Office of Price Administration—the wartime organization that directly

impacted the life of every man, woman, and child in this country during World

War II. v

Sources:

“Certificates Are Awarded” – The Wellsboro Gazette (Wellsboro PA), 17

Jan 1945.

“OPA Honors Helpers” – The Van Nuys News (Van Nuys CA), 30 Dec

1943.

“Question Box” – Homemakers’

“Ration Board Clerks Given Silver Pins”

– The Times (

“Service Pins and Ribbons” – The Wellsboro Gazette (Wellsboro PA), 17

Jan 1945.

“Some Observations on Rationing” by

Charles F. Phillips – American Economic

Growth: The Historic Challenge,

edited by William F. Donnelly, S.J., University of Santa Clara, MSS Information

Corporation, New York NY: 1973.

“State OPA Honors Merchant on

“Volunteers for OPA Duty to Receive 482

Awards in District” – The Clare Sentinel

(Clare MI), 7 Jan 1944.

“War Price and Ration Boards to Get

Awards” –

“500 Eligible for Citations” – The News Journal (