United States Army

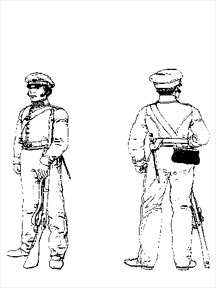

Infantry

Enlisted Man's Uniform 1843-1851

This booklet was produced and published by the Ghost Garrison, a volunteer,

non-profit organization.

In 1832 Secretary of War Lewis Cass established the Clothing Bureau within

the War Department, thus formalizing the responsibility of the Quartermaster General.

The outbreak of the war with Mexico

brought problems in clothing administration, mainly in terms of the

availability and timely production of garments for use by the regular and

volunteer forces fighting the war.

The primary place of manufacture was the Schuykill

Arsenal in Philadelphia, and the

coming of the war strained its production capabilities. Nonetheless, the staff

at Schuykill, augmented by wartime workers, succeeded

in meeting the emergency requirements. Under production guidelines, cloth, buttons,

and similar appurtenances were purchased from private suppliers and turned over

to seamstresses to make into garments. Shoes were also produced at the arsenal,

although many pairs were supplied under civilian contract. After the war, Schuykill continued to manufacture clothing for the army.. Aside from the emergency of the war with Mexico,

procurement at Schuykill during the 1840's and 1850's

was largely successful because of the small size of the army.

"Dark blue is the national color". Such are the opening words of

the uniform regulations of 1821. Yet during the Mexican War the fatigue suit of

the foot soldier was entirely sky-blue. Dark blue cloth implied a relatively expensive, smooth, finely woven broadcloth,

dyed in the cloth, while sky-blue meant a much cheaper, rougher material, often

dyed in the thread and woven afterward. Dark blue, in some minds, stood for

formal dress parades; whereas sky-blue meant field soldiering. Sky-blue was

also much easier to procure and much less expensive. Dress regulations refer to

the color as "white and light blue mixed, commonly called sky-blue

mixture". The enlisted man's uniform the world over until the twentieth

century was wool or wool mixed with cotton or flax. Kersey was a rough, coarse

cloth woven of wool, usually ribbed, that was used extensively for regular army

clothing.

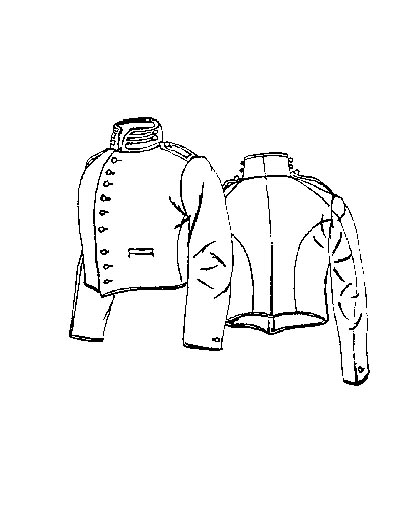

Shell

or Fatigue Jacket

The Infantry uniform was basically a sky-blue color and made of wool kersey.

In the early 19th century the shell jacket was a single breasted garment which

reached about an inch or two below the waist. It had a standing hooked-up

collar three inches high. There were nine white pewter buttons down the front,

one on each sleeve cuff and two on each side of the collar. It was also fitted

with cloth shoulder straps each fasted with one button. The Infantry fatigue

jacket had white binding on the collar and also on the shoulder straps. During

this time period white was the color which designated Infantry. For every five

years of faithful service the soldier could wear a white chevron, point up on

each upper arm. War service was indicated by a narrow red edge on this chevron.

Chevrons were not used to designate the ranks of sergeants and corporals.

·

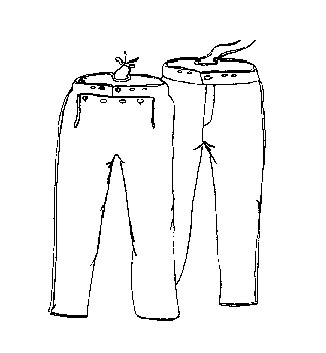

Issue Trousers

or ‘Trowsers"

Army issue trousers were made of sky-blue kersey. They were worn straight

and cuffless, creasing was not known. Most trousers

were fitted with a fall front which was a carry over from earlier times. The

fly front began to appear shortly after 1842. All trousers were equipped with

suspender (brace) buttons. The back of the waistband had a four inch slit with

a drawstring to permit further adjustment for waist size. The cut of the

trousers brought the waistband well above the hip. Trousers for Infantry had a

one inch slit at the bottom of the leg to assist in pulling them over heavy

shoes. On the sky-blue trousers, a white stripe down the outside seam of each

leg designated a sergeant.

Summer

Duty Uniform

The 1839 regulations prescribed a new summer white undress uniform made of

cotton. The jacket and trousers were cut identical to the sky-blue woolen

fatigues. During the conflict with the Seminole Indians in Florida,

the Infantry was issued the usual woolen uniform. There were so many casualties

from the excessive heat that in 1835 a new white cotton uniform was provided

for all troops serving south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

This new cotton uniform proved so popular and was so inexpensive to produce

that by 1839 it was made available to all soldiers and was worn from the end of

April to the end of September.

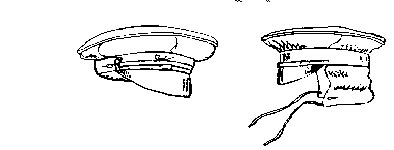

Forage

Cap

The forage cap worn by all regular troops was the one commonly associated

with the Mexican War. It was a dark blue cloth cap with a soft crown which was

wider than the headband. A reed was sewn into the crown welt to provide some

stability to the rounded configuration. This reed was often removed by the

soldier to give the cap a carefree or jaunty appearance. The cap had a leather

visor and chin strap. It was fitted with a neck cape which was folded up on the

outside of the headband and tied on the front. This

‘Model 1839" cap was issued until about 1855. There were

several variations in this fatigue cap; the main difference being in the slope

of the visor. The earlier Type I had a nearly vertical visor while in Type II

the visor assumed a more horizontal placement. This later style saw very little

use.

Footwear

The shoe for the Infantry was called an ankle boot or a bootee. This was a

high quarter shoe with five to six eyelets for laces. It was made of black

leather with the smooth side out. During this time period all footwear for men

had very blunt or square toe. The Jefferson boot or

brogan that was issued during the Civil War was a bit lower on the ankle than

this early shoe.

Issue

Shirt

This pull-over type of shirt had either a standing or a fold down collar. It

was fastened at the neck with two or three bone buttons. The sleeves were

rather full and were closed at the cuff with one button. These shirts were

usually made of muslin, flannel and sometimes wool. Most of them were white or

gray and they closely followed the popular civilian styles. This shirt was also

called an under shirt in the 1840s but is not to be confused with what we call

an undershirt today.

Neck

Stock

Black leather neck stocks were prescribed for enlisted men in all dress

regulations and a patent was taken out for a new style as late as 1858. Army

medical officers spoke rather scathingly of its great inconvenience and the

frequent injury it did to the men. But, the stiff leather stocks continued to

be worn because Uniform Regulations called for them. They were just an object

of fashion similar to the cravat and the necktie. The neck stock was worn over

the standing collar of the shirt and under the jacket. Most stocks were shaped

to fit the contour of the jaw and the chin.

Greatcoat

The overcoat was an item long considered necessary for regular issue to

troops. For all enlisted foot soldiers the greatcoat was made of sky-blue

kersey with a blanket lining which reached to the waist. It had a standing

collar and a cape which fell to the elbow. The coat had a five button front and

six buttons on the cape. There is a butted belt in the rear. The cape could be

thrown over the head, parka fashion, during severe weather and long cuffs which

could be pulled down to offer additional protection for the hands. The bottom

of the greatcoat was not hemmed.

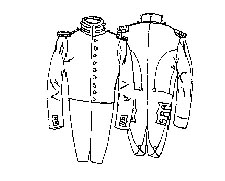

Dress

Coatee

The dress coatee was smart and military, designed

for occasions when the soldier might be viewed by the public. This dark blue

woolen coat resembled the tail coat of earlier periods. It was padded across

the chest, cut off in the front just below the waist and had long skirts in the

rear. The standing collar was at least two inches high; regulations called for

it to be as high as possible while still allowing the chin to turn freely. Both

the collar and the cuffs were piped in white and the tails featured white turnbacks. The coatee was closed

with a single row of white pewter buttons . It went by

many nicknames, among them ‘spiketail', ‘clawhammer' and ‘tail coat'. This dress coatee remained in use until the uniform regulation changes

of 1851.

Dress

Shako

This shako first appeared in 1832 as a replacement for the massive bell

crowned ‘tar bucket' shako of 1821. It featured a patent leather top,

visor and chin strap. The cylindrical body was of black felt. The white plume

was of ‘cut feathers' or wool and was fastened to the cap by a brass

fitting called a tulip because of its shape. Cap insignia consisted of a brass eagle

and a silver Infantry bugle; within the triangle formed by the bugle and its

suspension cord was placed the regimental number.

Cartridge

Box

The essentials of a military cartridge box were several. It had to be stout

enough to stand abuse and to prevent the fragile paper cartridges of the day

from being smashed. It had to be waterproof enough to shield the ammunition

from snow and rain. It had to present the cartridges in a fixed position so

that the soldier could find one in the excitement of battle with a minimum of

fumbling and without looking around. The regulation Infantry cartridge box was

made of black bridle leather and contained a wooden block that was drilled to

accept 24-26 cartridges: under the block was a tin tray to hold extra

cartridges, extra flints and cleaning cloths. Near the middle of the nineteenth

century this wooden block was replaced with two tin inserts which held twenty cartridges

in an upright position plus an additional twenty cartridges in two reserve

packages. The lid of the early style box was unadorned while a brass U.S.

plate similar to the waist belt plate was attached to the flap of the later

models: This additional weight aided in keeping the unhooked flap in a closed

position when the soldier was running during combat. The seams of the cartridge

box were designed so that the force of an accidental explosion of its contents

would blow outward, away from the body of the soldier. The cartridge box was

suspended by a white buff leather belt over the left shoulder which permitted

the box to rest upon the right hip. A round brass

‘Eagle" plate was attached to the shoulder strap in a position to

place it at the center of the chest.

Haversack

On field service every soldier was issued a haversack or ‘bread bag'

in which he carried his rations and eating utensils. It was a plain white

canvas envelope with a flap secured by three pewter buttons. This haversack was

slung over the right shoulder and rested on the left hip.

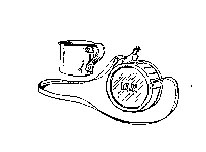

Canteen

and Cup

One of the most personal of all items of equipage was the canteen or water

jug. The usual issue canteen was a wooden keg shaped somewhat like a very short

barrel. The ends or heads were of solid wood while the sides were made of

staves held in position by hoops of wood or tinned iron. White oak was the

preferred material for canteen construction since it did not render an off

flavor to the water. Spaced around the side of the canteen were three loops of

leather or metal for attaching a white canvas sling. The entire canteen was

painted sky-blue and the letters U.S.

were stenciled on one head. The canteen was carried on the left side atop the

haversack which served as a cushion to the soldiers

hip. The large government issue cup was used both as a

mess cup and as a drinking cup. It was sturdily constructed, the handle and rim

being re-enforced with wire. On field duty the cup was often suspended from the

canteen sling strap. Bayonet

Scabbard

The scabbard for the triangular socket bayonet was made of black bridle

leather with a brass tip. Originally the bayonet scabbard was carried on a

shoulder strap which hung from the right shoulder and crossed the cartridge box

strap in the middle of the soldiers body. In 1841 a

white buff leather waist belt was issued to help secure both the cartridge box

and the bayonet scabbard. Then for reasons of practicality and economy the

bayonet shoulder strap was eliminated and the bayonet scabbard was attached to

the waist belt by means of a sliding white buff leather frog. The bayonet

scabbard was worn on the left side of the body.

Waist

Belt

The white buff leather waist belt was one and one half inches wide and

usually had a leather loop on the left end. To the other end was attached an

oval brass plate stamped with the raised letter U.S.

Even thought the waist belt might be too long, regulations did not permit it to

be cut. The waist belt was originally intended to secure the cartridge box and

the bayonet cross belt rig to the body. Within a few years of its introduction

it replaced the shoulder belt as a means of carrying the bayonet scabbard.

Belt

Plates

The regulation U.S. Army cartridge box suspension strap had a circular

‘Eagle" plate attached so as to be centered on the soldier's breast.

It served no function other than decoration. This ‘Eagle' plate, more

than any other single item, designated the soldier as an Infantryman. The plate

was issued for over thirty years with virtually no change in design. It had a

raised rim surrounding an eagle holding three arrows and an olive branch. It

was of thin stamped brass with a lead filled back into which were imbedded the

devices for attaching it to the belt. The waist belt was fastened in the front

of the soldier with and oval plate or buckle made of thin stamped brass that

had a soft lead backing. The face of the plate was imprinted with the letters

U.S. Cartridge boxes designed to contain the tin inserts were decorated on

their flap with a similar U.S.

plate.

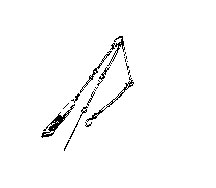

Pick

and Brush

An iron pick and a bristle brush were issued to each Infantryman for field

cleaning the flintlock vent and pan of his musket. These items were suspended from

the front of the cartridge box strap by a series of brass links. It was often

looped over the cartridge box strap to keep it from becoming entangled. This

pick and brush was first issued in 1816 and continued to be used as long as the

flintlock was in service.

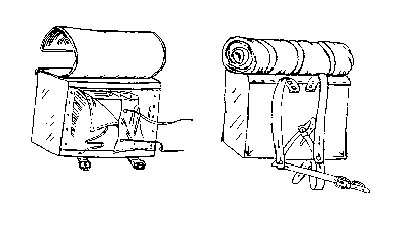

Knapsack

Knapsacks were issued to all Infantrymen and other soldiers who habitually

served on foot. The soldier on field duty was supposed to pack on or in his

knapsack a wool blanket, extra shoes, spare clothing, mess equipment and toilet

articles. This ridged frame knapsack was constructed around a frame of white

pine covered with black painted canvas which was tacked on. Two inner flaps,

which tied in the center, closed the box. An outer flap of leather buckled at

the bottom covering the exposed rear of the knapsack. Three straps on the top

of the knapsack held a rolled blanket which ranged in color from red to a faded

wine color. A unit number was usually painted in white on the back outer flap.

The ridged frame knapsack was preferred in the early nineteenth century because

even when it was empty it presented a very neat military appearance.

Musket

The U.S.

flintlock musket, Model 1816, was the earliest shoulder arm to have been used

in large numbers by Federal troops. It was a long barreled smoothbore of .69 caliber. The Model 1816 was produced at the Springfield

and Harpers Ferry Arsenals and also by a variety of private contractors. With a

very few variations this musket continued to be produced until 1844. From 1848

through the early 1850s all those muskets deemed suitable were recalled and

altered to the percussion system. The M1816 was 58 inches in length and weighed

about ten pounds without the bayonet. The lock featured a detachable brass pan.

Three flat bands helped to secure the barrel to the full length black walnut

stock. A bayonet lug was attached to the top of the barrel. In the final

version of this musket, produced from 1831 until 1844, all metal parts were

finished in the bright; official correspondence refers to this as

‘National Armory Bright'.

Bayonet

The socket bayonet was made without a clamping ring. It had a three inch

socket and a sixteen inch triangular blade. The top face of the blade was

fluted for slightly more than half of its length. The entire bayonet was

finished in the bright.

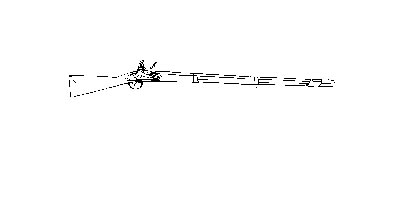

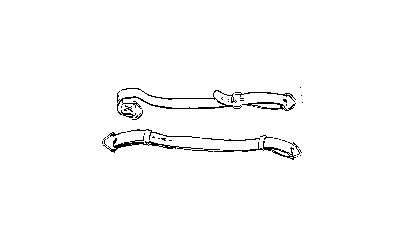

Musket

Sling

The gun sling provided an alternate method of carrying the musket, usually

while on the march or on campaign. It was a russet strap one and one quarter

inches wide and forty six inches long. It had one sliding loop and one fixed

loop. Adjustment was made with a brass hook and a series of regularly spaced

holes. Some units were apparently still being supplied with an earlier model

made of white buff leather; one end being fastened with a leather thong and

roller buckle providing a means of adjustment for length.

Sources of Information:

Albert N. Hardin, ‘The American bayonet, 1776-1964'; Philadelphia, PA,

1977 Frederick P. Todd, ‘American Military Equipage, 1851-1872', Vol. 1;

Providence, RI, 1974. Sidney B.Brinkerhoff,

‘Boots and Shoes of the Frontier Soldier' ; Tucson,

AX, 1976 Randy Steffen, ‘The Horse Soldier 1776-1943', Vol. I; Norman,

OK, 1977 Philip R. Katcher, ‘The Mexican-American

War, 1846-1848'; London, Great Britain, 1976 John R. Elting,

‘Military Uniforms In America', Vol. II; San Rafael, CA, 1977. Edgar M.

Howell &Donald E. Kloster, ‘United

States Army Headgear To

1854', Vol. I; Wash. , D.C., 1969 James E. Hicks, ‘United

States Military Firearms'; La Canada,

CA, 1962. Robert M. Reilly, ‘United States Military Small Arms, 1816-1865'; Baton Rouge, LA, 1970.

The Ghost Garrison is established as a historical education group which has its

primary objective, the growth of individual and public knowledge relative to

the military history of the territory and state of Iowa, and the soldiers who

were Garrisoned within Iowa, and the part they played in the protection,

development, and social fabric of Iowa in the 1840's and 1850's. The volunteers

of this organization conduct research, exchange appropriate information and

provide living interpretations and programs. The Garrison wear authentically

reproduced uniforms and equipment and camp in a military style camp appropriate

to the 1840 time period.

Among the many events that the Garrison participates in each year are two

annual events. In Fort Atkinson, Iowa

on the last weekend of September the Garrison portrays K company of the 1st

U.S. Infantry and B company of the 1st U.S. Dragoons.

In Fort Dodge, Iowa

on the 1st weekend of June the Garrison portrays E Company of the 6th U.S.

Infantry.

The Ghost Garrison is a volunteer, non-profit organization consisting of

members throughout Iowa. Anyone

who is interested in enlisting in the Garrison as a participant or who would

like to inquire about having the Ghost Garrison appearing at an event may

contact:

Fort Dodge Historical Foundation & Trading Post S. Kenyon & Museum

Rd Fort Dodge, Ia 50501

phone: 515 573-4231

email: dmackay@dodgenet.com

|

Space for this Web

site provided courtesy of Dodgnet of Fort Dodge,

IA.

|

|

|

The material on this page and my

other page is under ownership of its respective writers. All Rights Reserved.